Whether directing august art museums or scrappy upstarts, he championed art-world outsiders and socially conscious and political art. He gave Yoko Ono her first solo show.

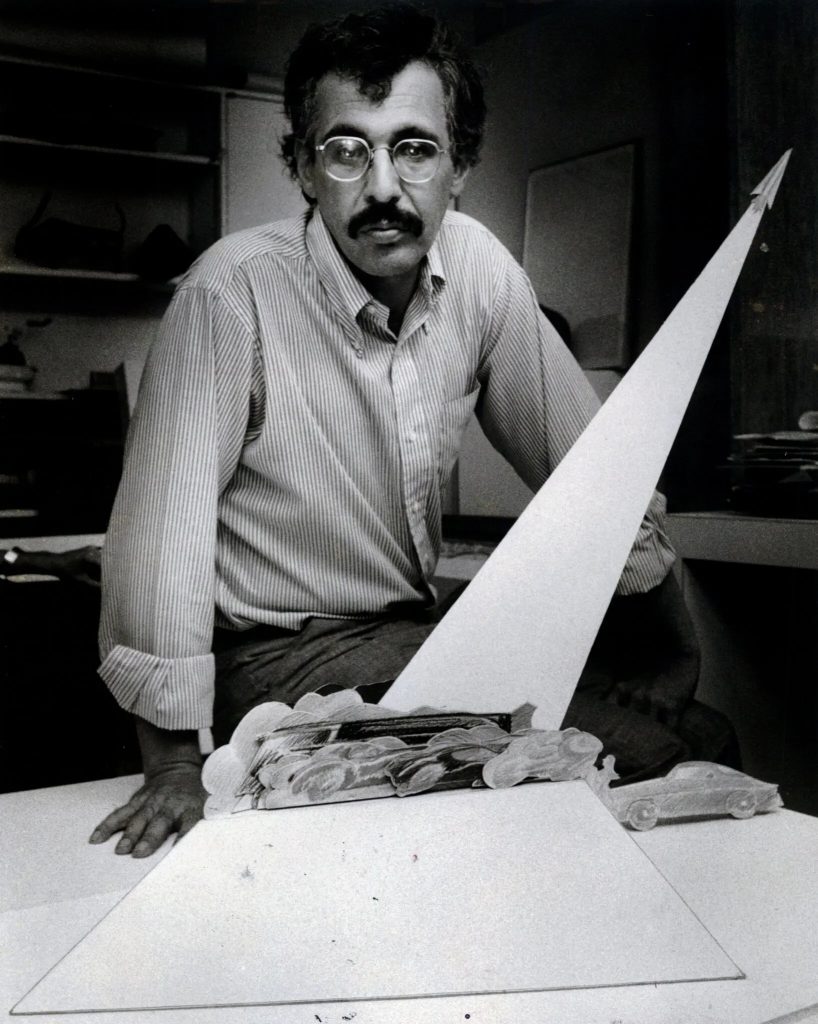

James Harithas, a celebrated museum director and founder who viewed curation as a form of activism, highlighting iconoclastic, often socially conscious work both by little-known artists as well as maverick luminaries like Yoko Ono and Nam June Paik, died on March 23. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by his sister, Paula Yankopoulos.

Mr. Harithas had been an aspiring painter as a youth, but instead he became an artistic force as the director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington in the late 1960s, before moving to the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, N.Y., and later the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston.

Never afraid to push boundaries or ruffle feathers, he fought to open the museum experience to artists and patrons well outside the insular establishment art scene.

“He looked outside the art world and its hierarchies to a much larger pool of artists whom he thought should have opportunities to present their work in a public forum,” Paul Schimmel, former chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, said in a phone interview. “It was his commitment to social justice, political change, the representation of minority artists that really made him stand out.”

While at the Everson in the early 1970s, Mr. Harithas (pronounced HAIR-i-thas) developed a workshop for inmates at the nearby Auburn Correctional Facility. Their work was ultimately shown in a 1973 exhibition called “From Within,” in collaboration with the National Collection of Fine Arts at the Smithsonian Institution, and even featured on the popular game show “To Tell the Truth.”

Around the same time, Mr. Harithas helped mount an exhibition of art made by leftist Sandinista rebels in Nicaragua. Decades later, he organized an exhibition of the work of Palestinian artists from Gaza and the West Bank at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston, which he and his wife, Ann Harithas, founded in 2001 as an “activist institution,” according to its website.

“Museums are as much involved in fashion and economics as they are art,” Mr. Harithas said in a 2008 interview with the arts publication The Brooklyn Rail. “But I must say I’m interested in artists, not museums. I think museums have failed to reach most of the people. We need new kinds of museums.”

He spent more than a half century trying to make good on his word.

Menelaus James Harithas was born on Dec. 1, 1932, in Lewiston, Maine, the oldest of three children of Nicolaus Harithas, a Greek immigrant who became a lawyer and judge, and Terpsichore (Seferlis) Harithas, an amateur painter and musician.

Young James spent several years living in occupied Germany, where his father worked with the U.S. military after World War II. He eventually returned to the United States to attend the University of Maine in Orono.

On a 1953 trip to Germany to see his parents, he experienced an epiphany at an Abstract Expressionist show in Frankfurt. “Oh, my God, here was pure spirit — so tangible and yet so mysterious,” Mr. Harithas told The Brooklyn Rail. “Within a month, I quit school and hitchhiked to New York.”

His stint in New York lasted only a year, consisting primarily of odd jobs and afternoons at the city’s museums. He then returned to Maine to finish his degree and later earned a master’s of fine arts degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1962, he met a curator who invited him to help mount an exhibition in Finland of young American artists. That got him started on a career as a curator, first at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Mass., and later at the Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona.

He joined the Corcoran in 1965 and rose to director three years later. From his perch at that august museum, Mr. Harithas was both a witness to and a participant in the anti-Vietnam War protests unfolding nearby, including the teeming March on the Pentagon in 1967.

That same year, the museum mounted its much-publicized “Scale as Content” show, featuring a sculpture by Mr. Harithas’s friend Barnett Newman called “Broken Obelisk,” a 26-foot-tall obelisk split in two, its upper half upended and teetering on a pyramid.

Editors’ Picks

Everything You Need to Know About the 2023 Met GalaWhy Are More Men Getting Perms?Is It T.M.I. for Entrepreneurs to Air Their Private Business?

Mr. Newman denied any political message behind the piece. Still, the placement of the giant steel sculpture outside the Corcoran, a short stroll from the Washington Monument, struck many as a clear commentary on shattered American ideals.

Mr. Harithas resigned from the Corcoran in 1969 in a dispute with the museum board over autonomy in creative decisions. He landed at the Everson two years later.

There he exhibited the work of artists he considered underappreciated, including Joan Mitchell and Norman Bluhm, as well as Ms. Ono. It was at the Everson, in 1971, that Ms. Ono had her first solo museum exhibition, “This Is Not Here,” bringing her avant-garde work to audiences who largely knew her only as the wife of John Lennon.

A pioneering force in video art, the Everson under Mr. Harithas mounted the first museum exhibit for Mr. Paik, titled “Video and Videa,” in 1972.

Mr. Harithas moved to Houston in 1974 to begin a four-year stewardship at the Contemporary Arts Museum. There he mounted exhibitions by Texas artists like James Surls and Lynn Randolph, as well as the first solo show by the Brooklyn-born Julian Schnabel, a Texas transplant.

Mr. Harithas married Ann O’Connor Williams, an artist and collector from a prominent ranching and oil family, in 1978, and the couple spent the following decades in Houston working to transform that brawny oil town into an art hub.

In addition to the Station Museum, in 1998 the couple opened the Art Car Museum in Houston, a working-class museum, as Mr. Harithas described it, devoted to automobile-based art. (In 2016, Ms. Harithas also founded the Five Points Museum of Contemporary Art in nearby Victoria, Texas, to celebrate regional artists and the cultural diversity of South Texas.)

By the end of his life, Mr. Harithas was “without a doubt the most influential force on the Houston art scene over the past 50 years,” as Pete Gershon, a local curator and art historian, described him to The Houston Chronicle.

Along with his sister, Mr. Harithas is survived by his daughters, Jeannie Harithas, Thalia Harithas and Lia Blyth, all from an earlier marriage to Christiana Baka; four stepchildren, Madeline Merrill, Molly Kemp, Stephanie Loeffler and Will Robinson; and two grandsons. Ann Harithas died in 2021.

Early in his career, Mr. Harithas realized the power of museums to change minds and, possibly, society. “I knew a museum was a political force,” he once said, one that he thought could have a strong social agenda, free from institutional conventions.

As he put it, “I felt that a museum had to be free-form.”

Leave a Reply